Kurt Vonnegut draws the shape of all great narratives

Kurt Vonnegut felt that all of the world’s stories—from the oldest fairytales to the next Spielberg blockbuster—have simple shapes that can be spat out by computers.

In what he regarded his ‘prettiest contribution to the culture’, the Slaughterhouse-Five author mapped the ups and downs of history’s greatest narratives as part of his rejected anthropology thesis.

In a section titled ‘Here is a lesson in creative writing’ in A Man Without a Country, Vonnegut hand-drew the emotional arcs of stories into five basic shapes:

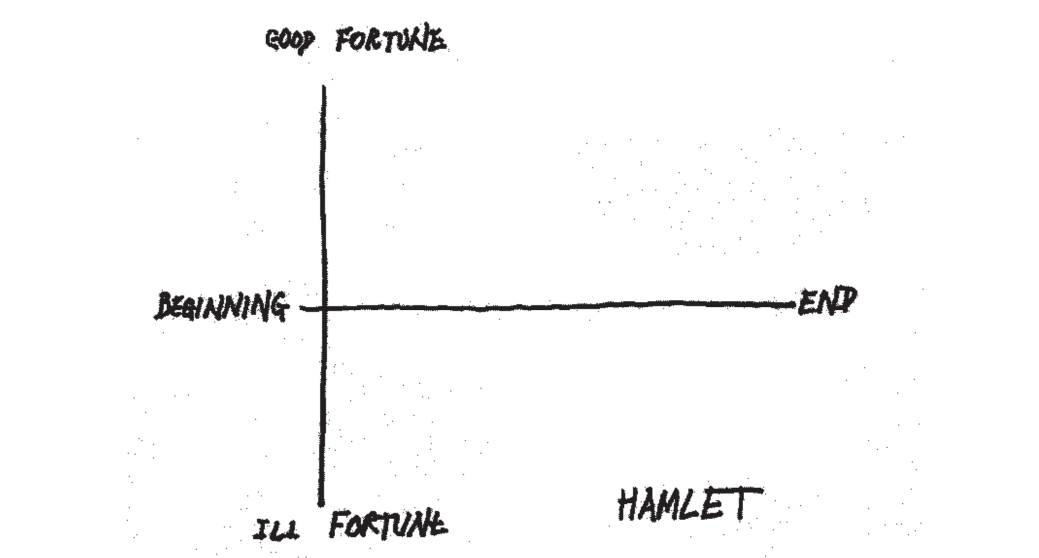

Good news or bad news?

Examples: Hamlet, Game of Thrones.

This fact that this narrative has no curves on it doesn’t mean that every writer that has ever used it, including Shakespeare, was a failure. In fact, it’s the most complex story arc to pull off successfully, because it’s the truest to life.

Like the ‘story of the Chinese farmer’, the ‘good news or bad news’ arc demonstrates that so many things can happen across a story, and life itself, that seems good or bad. Lost jobs, bad haircuts, missed buses… The truth is, you may later learn that these misfortunes steer the course of your life to something positive. It’s impossible to know otherwise, and this unpredictability adds much-needed tension to a narrative.

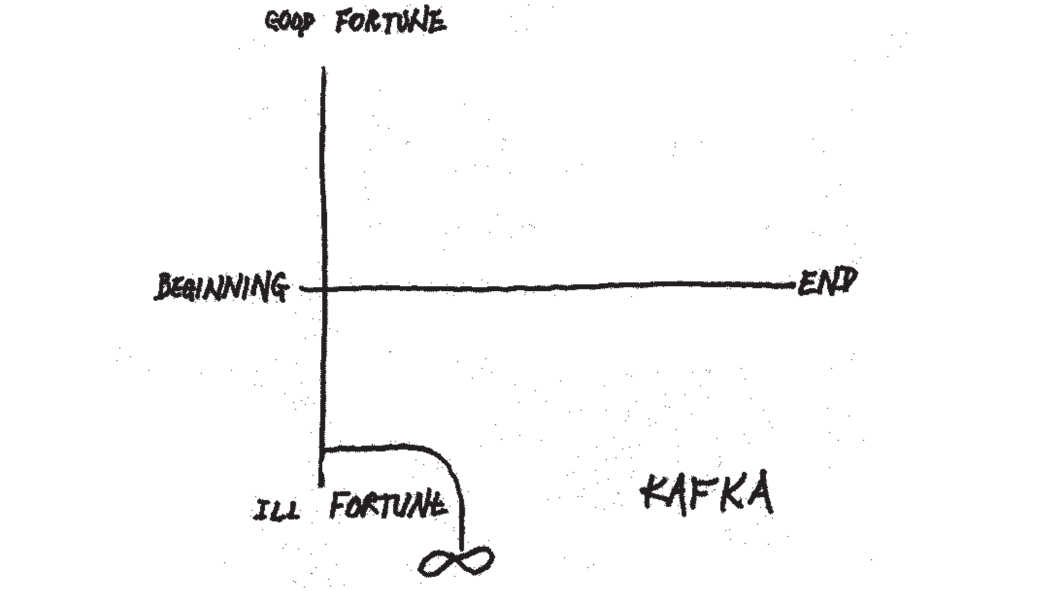

From Bad to Worse

Examples: The Metamorphosis, Black Mirror.

When approaching a ‘from bad to worse’ arc, you should try to picture a character’s personal hell, and then times it over and over ad infinitum. According to Vonnegut in his 8 rules to write a short story, you should always ‘make awful things happen’ to characters. But in the end, it’s up to you whether you bring them out of it.

Kafka must have hated his characters. George Orwell when writing 1984, likewise. But what makes a ‘from bad to worse’ story so compelling is that through it, you can capture the darkness of the world and its inhabitants with sardonic humour.

Boy meets girl

Examples: The Notebook, Jane Eyre.

This narrative arc needn’t be about a boy finding the girl, losing the girl, and then getting the girl back again. It could be ‘millionaire loses money’, or ‘writer loses talent’, or ‘old man loses hat’.

The principle is that someone gets something wonderful, feels destroyed without it, and wins it back again. The key is that with all narratives, the audience must feel pity or fear for that which is lost.

Man in Hole

Examples: The Godfather, Harold and Kumar.

The ‘man in hole’ narrative has what everyone is looking for in their own personal story -- to overcome their struggles and end up better-off on the other side.

If you’re also looking to earn top-dollar, this is the story for you. After analysing data from 6,147 movie scripts, Cornell University discovered that the ‘man in hole’ story arc, with its up-down-up trajectory, earned the highest on average of all movie genres.

Cinderella

Examples: Cinderella, Pride and Prejudice.

Similar to ‘boy meets girl’, but with a few upward steps. Specifically, a beautiful dress, eyeliner, and a pumpkin-spiced means of transportation.

When midnight strikes, Cinderella’s fall is steep but not as low from where she started. She will live with the memory of that night for the rest of her life. When the prince arrives with the slipper, she achieves off-scale, dreamlike, infinite happiness.

Understanding humanity through narrative forms

After witnessing the destruction of Dresden during World War Two, Vonnegut tried to make sense of human behaviour by understanding these narrative forms in his own unusual anthropological study.

In the end, patterns of gain and loss across our lives can mimic the ups and downs of our favourite movies and novels. And even if much of our lives represent the straight line of ‘good news or bad news?’—with all the queues when grocery shopping and hours browsing YouTube—it’s important we capture the ups and downs in their fascinating turbulence.

We may never fully understand what our individual story means, but we can, as Vonnegut said ‘help each other through this thing. Whatever it is.’